(Jewish Group) Tevye der Shvartzer Khazn [View all]

Icame across the story of Thomas LaRue Jones by sheer accident. The year was 2015. Removed from the din that surrounded the first coming of Black Lives Matter, I was immersed in the YIVO archive in New York selecting theatrical posters for an exhibition, New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway, at the Museum of the City of New York. The names buzzing through my head were (Boris) Thomashefsky, (Jacob P.) Adler, (Maurice) Schwartz, (Molly) Picon, and other celebrities of the old Yiddish stage. Working my way through a mass of colorful theater posters that featured Yiddish divas and matinee idols, I glimpsed an old black-and-white illustrated placard with a cameolike portrait of a serious-looking young Black man with soulful eyes, dressed in festive cantorial regalia. Titled “Tevye, der shvartzer khazn” (Tevye, the Black Cantor), he was, the undated print declared, “The Greatest Wonder of the World.” A small-type English-language byline at bottom of the poster announced that “Thomas La-Rue” was “the most phenomenal cantor-tenor in America” and “the only one of his kind in the world.” “Tevye,” the renowned Black cantor, the poster announced in Yiddish, “has taken America by storm” with a multilanguage repertoire of Jewish folk songs and cantorial compositions by Yossele (Joseph) Rosenblatt and other Jewish composers.

The 1920s were an opportune time for Tevye LaRue Jones to make his entrance. Cantorial performance was flourishing in America. Cantors were no longer confined to the sacred space of the synagogue. They recorded their music, at times accompanied by musical instruments which would not be allowed in the synagogue. Even women who would not be allowed to sing in the synagogue were performing hazzones on stage. Hundreds of records of cantorial music were produced, avidly consumed by a public that was also packing concert halls and vaudeville venues where cantors performed. Outside the synagogue the cantor was no longer serving merely as a “shliakh tsibbur,” the voice of his community, but also as a seasoned entertainer whose repertoire often broadened to include folk and Yiddish theater songs. In this thriving popular Jewish culture, a Black cantor would likely prove an attraction.

So, who was this “Black Cantor”? Jones’ name does not appear in books on the Yiddish stage nor is it listed in Zalmen Zilbercweig’s comprehensive Lexicon of the Yiddish Theatre. But thanks to old, digitized newspapers, the mystery began to slowly unravel. Jones was a native of Newark, New Jersey, a city with substantial Jewish and Black communities. Endowed with a pleasant voice, the teenage Jones began a fledgling performance career singing Yiddish songs in local Jewish festive events. As early as 1915, a local Newark newspaper mentions his name, along with several other very Jewish-sounding names, as providing the entertainment for a Jewish wedding. A year later, the paper mentions his name as the person providing musical entertainment at another Jewish event.

---

Jones died in 1954, buried in an unmarked grave. Henry Sapoznik, anxious to secure a lasting memorial, raised funds for a proper monument. The unveiling of a commemorative headstone took place on Aug. 29, 2021, at the Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey. It was attended by 20 people who came specially to pay their respects to a long-forgotten performer. Though not Jewish, the ceremony and the headstone recognized the way that a sense of Jewish identity had shaped the singer’s life and his work, even if the songs he sang inevitably meant something different to a Black man from Newark than they did to his Jewish American audiences.

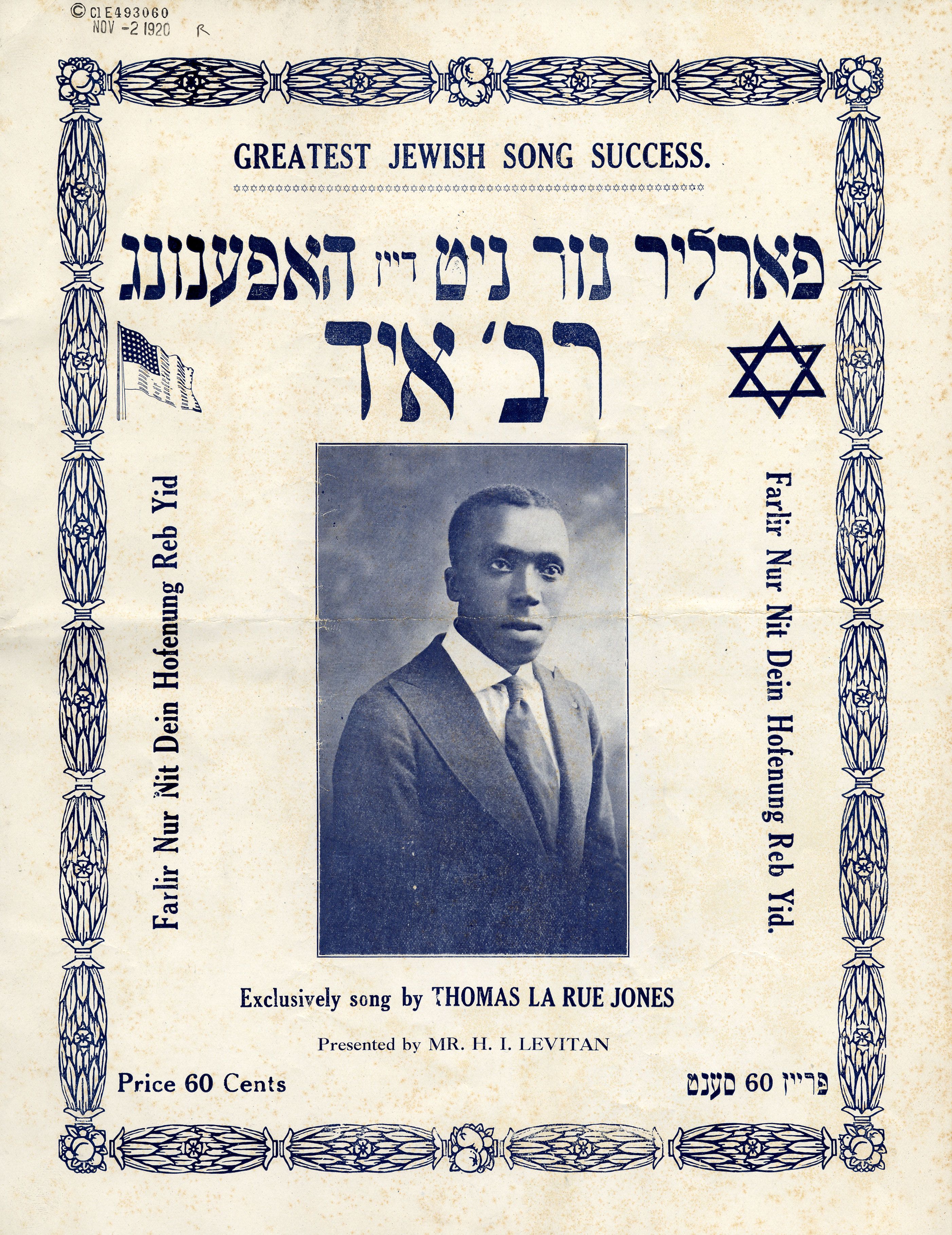

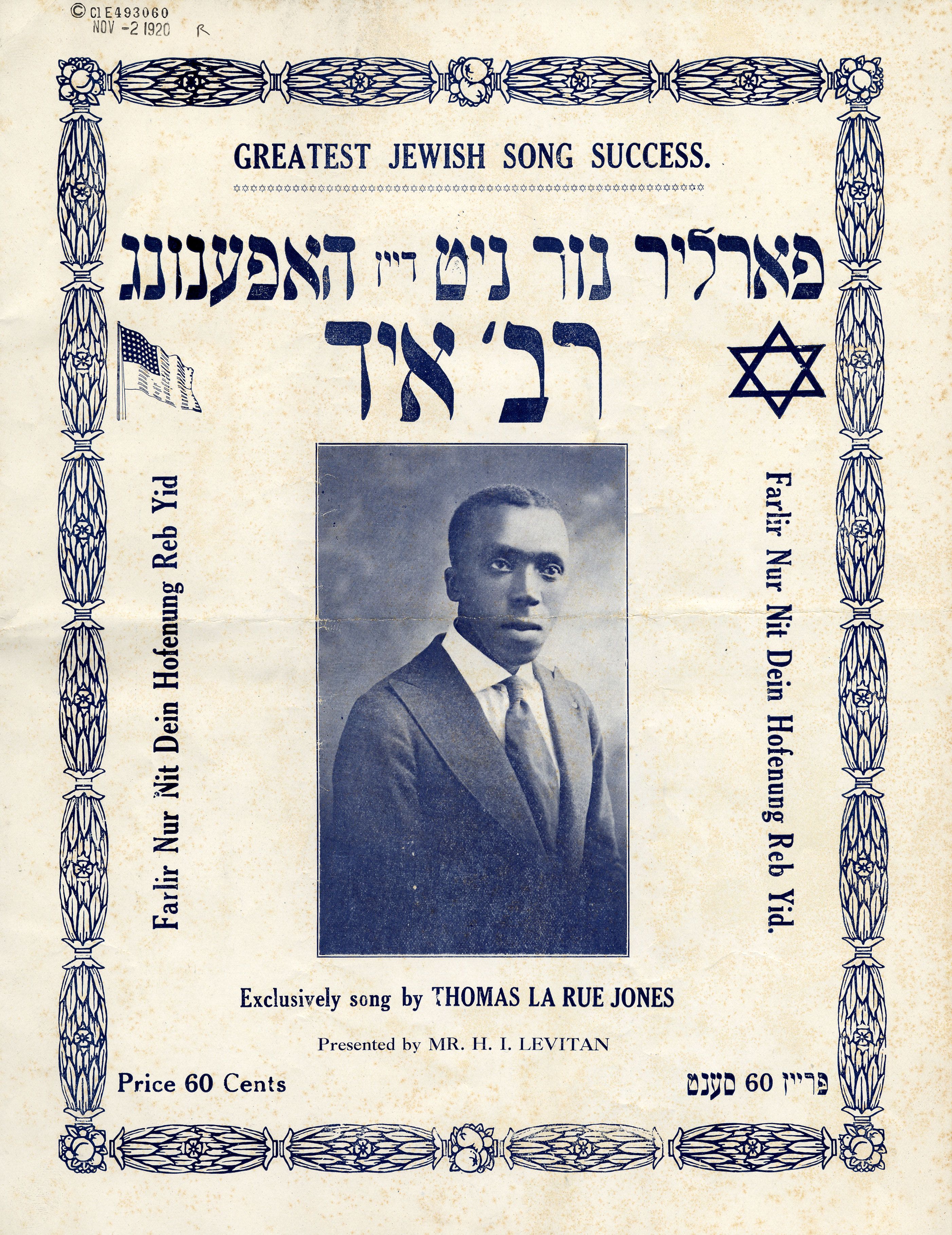

Thomas LaRue Jones’ portrait on the cover for ‘Ferlir nur nit dein hofnung reb Yid,’ 1920LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MUSIC DIVISION

more...