Science

Related: About this forumAn Interesting Experiment in Trying to Involve Journalists in Reporting Real Science Correctly.

One of the standard half-serious jokes I often repeat in my writings here when confronting articles from journalists linked and discussed here, typically about energy and the environment which are often sensationist and misleading, is that "One cannot get a degree in journalism if one has passed a college level science course with a grade of C or better."

Journalism, as is the case in the American political disaster in which journalists have been and are actively working to normalize an intellectually deficient and declining criminal fraud as a Presidential candidate, while demeaning as "too old" an activist highly functional President, is generally horrible where scientific issues are involved. One result of this marketing of bizarre ideology by journalists is climate change. I regard the major issue in climate change to be selective attention, for example, the magnification of the views of extreme scientific minorities in climate denial, or the demonization of nuclear energy, which I continue to insist is the last, best hope for humanity.

Thus it was with some interest that I came across this paper in a scientific journal in which scientists involved themselves with, and reviewed, journalism in connection with a very serious issue, PFAS (Per/Poly Fluorinated Alkylated Substances) contamination in Europe: PFAS Contamination in Europe: Generating Knowledge and Mapping Known and Likely Contamination with “Expert-Reviewed” Journalism Alissa Cordner, Phil Brown, Ian T. Cousins, Martin Scheringer, Luc Martinon, Gary Dagorn, Raphaëlle Aubert, Leana Hosea, Rachel Salvidge, Catharina Felke, Nadja Tausche, Daniel Drepper, Gianluca Liva, Ana Tudela, Antonio Delgado, Derrick Salvatore, Sarah Pilz, and Stéphane Horel Environmental Science & Technology 2024 58 (15), 6616-6627

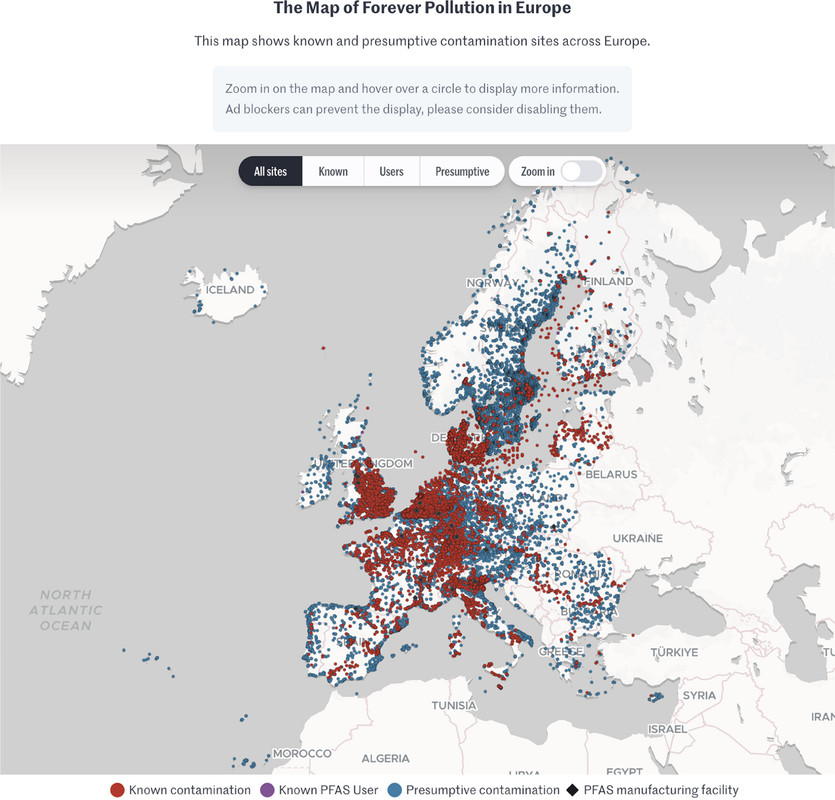

Unfortunately I will not have much time to discuss this paper in much detail, but a few excerpts and a graphic follow.

From the introduction:

PFAS have been broadly detected in environmental media including surface water, groundwater, raw and finished drinking water, soil, air, landfill leachate, sewage sludge, food, and dust. (12−15) As examples, a recent analysis of tap water samples in the United States collected between 2016 and 2021 detected PFAS at 45% of tested locations, (16) and the 2019 French National Biomonitoring Programme measured serum levels of 17 PFAS and detected PFAS in 100% of the 993 participants. (17) It has been argued that PFAS have exceeded a “planetary boundary” of “widespread and poorly reversible risks associated even with low-level PFAS exposures” since global rainwater samples have PFAS levels above proposed regulatory limits designed to protect public health... (1)

...In addition to data gaps due to a lack of testing, the present study was motivated by two additional data gaps. First, unlike in the US where many PFAS testing datasets have been made public by federal and state governments, academic research groups, and environmental advocacy organizations, (19−22) there were very few publicly available data on PFAS contamination across the EU. Second, in most cases, legal protections for industry trade secrets and confidential business information prevent the public from knowing where PFAS are used and emitted. (23,24) An exception to this is the US Toxics Release Inventory program, which has required reporting since 2020 by some firms in a subset of industries for a small number of PFAS. (25) But in most cases, even if a specific company is known to produce and/or use PFAS, it is difficult or impossible for the public to know whether PFAS are used at individual facilities...

The authors enlisted five investigative journalists in five countries, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and The Netherlands, in the "FPP" or "Forever Pollution Project" and paired them with a team of PFAS scientists, noting " journalistic projects aiming at generating data in collaboration with scientists rather than reporting on already-produced data are not common."

Not common, indeed. I would expect that most scientists feel as I do, that science journalism (except generally when it appears in major science journals) that journalism is oblivious when reporting science.

Further down in the article:

The map which is interactive in the full paper, and, I think, at the link given in the caption but cannot be so here:

The caption:

I don't expect journalism to become a serious mirror of reality in my now short remaining lifetime, but we have to start somewhere; we have to try something, and I applaud this effort.

I wrote earlier today about PFAS and the very dangerous "hydrogen will save us" fantasy often hyped in the scientifically illiterate media earlier today:

A Brief Note on the Toxicology Associated With Hydrogen Fuel Cells.

Have a nice Sunday afternoon.

GreenWave

(9,203 posts)And at my Alma Mater, broadcast journalists had to get a B or better in foreign language so as not to embarrass one and all when they need a name or say "whoo n tah" correctly. (junta,![]() )

)