Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Artists

Related: About this forum

2 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

Nighthawks by Edward Hopper: Great Art Explained (Original Post)

Uncle Joe

Aug 2021

OP

question everything

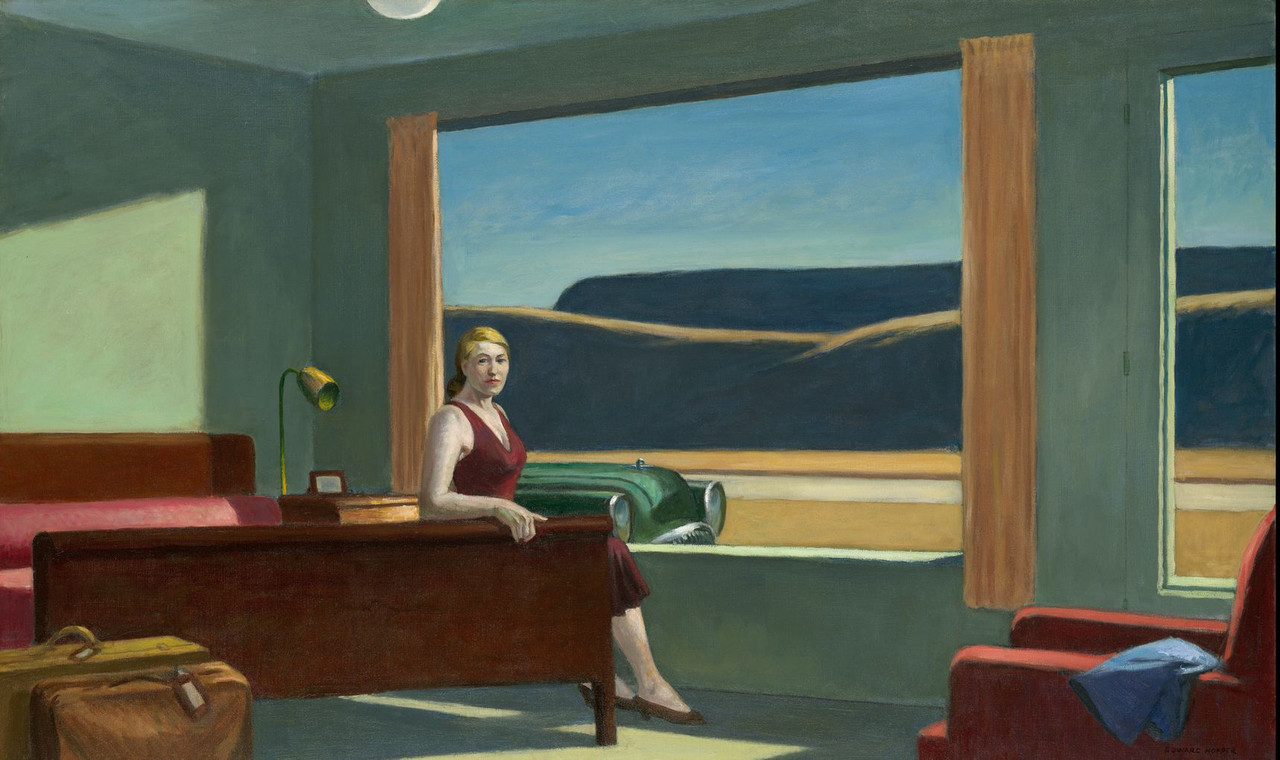

(51,564 posts)1. Enigmatic Isolation - Western Motel

Travel usually induces a sense of connection, but it may also enforce a feeling of aloneness. The paintings of Edward Hopper (1882-1967) are 20th-century embodiments of such isolation. His images of people, single or in small groups, represent what he called, in his description of the much reproduced “Nighthawks,” “the loneliness of a large city.” That loneliness existed for Hopper everywhere, not just in cities: in small towns, countryside and seaside, even in more desolate areas.

Consider the 1957 “Western Motel” (roughly three by four feet) at the Yale University Art Gallery, a picture of a woman sitting on a bed, with suitcases visible at its foot and a parked car visible through the window behind her. It shares a wall with three equally great Hopper oils: “Rooms for Tourists,” “Sunlight in a Cafeteria,” and “Rooms by the Sea.”

And like many of Hopper’s best pictures, even those without people in them, it invites us to infer or imagine a story. Brilliantly colored, awash with light, it also is darkened by mystery. It inspires questions: What time of day is it? What is the piece of clothing on the lower right? (Perhaps the woman’s jacket, but we cannot be sure.) Is she leaving the motel, or has she just arrived? Is she waiting for someone, probably her man? The bed is made, suggesting that she has just arrived. The bags are packed, which might imply she is leaving. Is her look cold, challenging, imploring? Stillness animates the scene. The room seems airless: The picture window does not open, although the second window, probably attached to a door, might. The Buick waits, like a steed. Is it hot outside in the desert?

(snip)

The picture is oddly flat. The large window seems like no barrier at all, the car almost nosing its way in. Everything looks boxy, even the Rothko-like clumps of color viewed through the smaller window. Long lines, vertical and horizontal, are accented by the rounding of the low-slung hills, the little globes of the car headlights, the ceiling fixture, the gooseneck lamp by the bed, and the woman’s rounded shoulders. The footboard is longer than it should be, skewing the geometry.

(snip)

“Western Motel” has one unique distinction. Josephine Nivison, whom Hopper married in 1924, was always his primary model. It is she who sits, ramrod-straight, impassive, on the bed, waiting. This is the only Hopper painting in which a person looks straight out at the viewer. Jo and her husband challenge us. “Look closely,” she seems to say. “We may be on the move, but right now we are a still life.”

https://www.wsj.com/articles/edward-hopper-nighthawks-western-motel-yale-buick-11628284714 (subscription)

=====

Just happened to read this yesterday, so thank you for the OP

StClone

(11,869 posts)2. Lack of egress and other enigmas

One quick view of Hopper's "Nighthawks" can leave a lasting impression. A studied view leads to seeing details, many covered by this fifteen-minute exploration. It answered one question I have always had of the diner's huge and impossibly large expanse of uninterrupted glass and the enigmatic "bend in the glass." It was to set the painting as a stage (which Hopper wanted) and the best way to capture that feel was with the glass as if it were not even there limiting the scene.